Selected Keeper's Log Articles

You can access a selection of articles from past issues of The Keeper's Log magazine here. Simply select from the sections below.

The tower of the old Cape Henry Lighthouse still stands, gaunt and silent, perched atop a dominating sand dune at the edge of the sea at the junction of the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Though its light is gone and repairs would be helpful, it continues as a noted, familiar and ancient landmark. Such it has been since its construction was begun in 1791.

No location is more emblematic of the blend—or clash, depending on how you view it—of Newport’s maritime past with modern development than Goat Island, where this modest and relatively ancient stone lighthouse stands alongside the massive Hyatt Regency Hotel. For almost 350 years, Goat Island, about six-tenths of a mile long in a north–south direction and now attached to the rest of the city by a causeway, has been utilized in just about every way imaginable—from fort to hotel, torpedo station to marina, barracks to condominiums.

One third of the way up the California coast from Mexico, the shoreline curves west and then makes an abrupt 90- degree tum north. Early on, this point of land - this cape, was tenned the Cape Hom of the Pacific. One 19th century marinei; sailing north in the relative calm of the Santa Barbara Channel, responded to a new seaman who thought the sailing conditions idyllic, "It may be fine now, but when we get north of Conception we'll catch hell!"

January 3, 1852, a maritime disaster near the entrance to Coos Bay brought the first white residents to the estuary. The Captain Lincoln, a coastal steamer carrying U.S. Army personnel to the newly established Fort Orford on Oregon's southwest coast, foundered in a storm and beached on the North Spit of Coos Bay. Although the castaways from this ship camped for nearly five months near their lonely wreck, they eventually left the region. Not until 1853 did settlers make permanent homes in the land of the Coos Indians.

This is the story of the Browns Point Lighthouse, which marks the hazardous shoal and north entrance to Tacoma’s Commencement Bay. This lighthouse is one of the lesser known lights of Puget Sound, and yet it has a history that we think you will find interesting.

In 1630 eleven ships came into Boston harbor, landing emigrants at Salem and Charleston. Up to that time it was the largest fleet of vessels ever seen in an American harbor. In those years Massachusetts was described by enthusiastic voyagers from England as the garden spot of the New England coast.

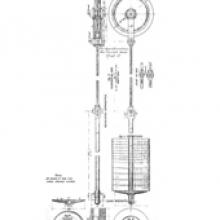

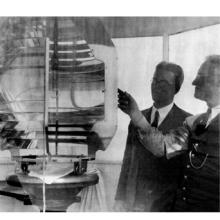

In the days before electricity and electric motors came to the shores, it was a weight-driven gearbox that provided the motive power to turn even immensely heavy Fresnel lenses to produce those flashes of light.

The frequent visits to the light stations by the district inspector were exciting and momentous events in the life of the keeper and his family. From the 1840s, still in the days of Stephen Pleasonton’s autocratic oversight of the Light-House Establishment, a system of periodic visits by inspecting officers was established. This became a much more formal process when the Light-House Board took over supervision of the Establishment in 1852.

Boon Island was named by the fishermen who, for many years left a barrel of food and clothing on the island every fall as a "boon" to any sailor who found himself shipwrecked on the lonely island. But the barrels rarely survived the first winter storm as the high point of the low rcky islet is only 14 feet above high water. Boon Island lies 6-1/2 miles off the southern coast of Maine and about eight miles from York, the nearest port. The island measures 200 feet by 700 feet and is devoid of any vegetation.

Point No Point Lighthouse has served mariners diligently since January 1880. Though small in stature as lighthouses go, it looms large in our nation’s history and bears the significant responsibility and noteworthy honor of welcoming ships to Puget Sound.