Selected Keeper's Log Articles

You can access a selection of articles from past issues of The Keeper's Log magazine here. Simply select from the sections below.

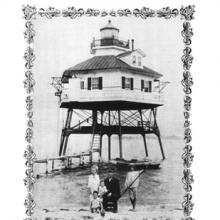

In 1853 Lieutenant A. M. Pennock, of the U,S, Lighthouse Board, filed a report on his survey of Chesapeake Bay. He commented that "a small light should be placed on Drum Point, inside of the Patuxent River." Work finally began on the lighthouse on July 17, 1883. The ten-inch-diameter, wrought-iron piles, made the Allentown Rolling Mills of Philadelphia, were fitted with three foot wide auger flanges. Each of the piles were laboriously hand-bored into the bottom of the Patuxent River like giant screws.

He has been called "overly critical" and "jealous of his uncle", even "liar". I speak of Issiah William Penn Lewis whose report on America's Lighthouse Service presented to U.S. Congress on February 24, 1843, was to rock the nation with a major scandal.

As the crow flies, the coastline of Georgia measures only some 100 miles, which doesn't give the state a whole lot of elbow room on the otherwise expansive Atlantic seaboard. One can be excused, therefore, from making the natural deduction that, with such a limited tract of oceanfront real estate, Georgia would have little in the way of lighthouse history and tradition. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Morris Island Lighthouse, nicknamed the Old Charleston Light, has served the citizens of South Carolina in various ways, for three centuries. The need for safe passage into Charleston Harbor was immediately recognized in 1670 when Albemarle Point was first settled.

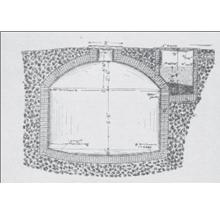

One of the most important aspects of America’s far flung light stations was the question of supplying water, not only for domestic use but, in some cases, for the boilers that supplied steam for sound (fog) signals.

Like many of its sister sentries on the West Coast, Lime Kiln Lighthouse had an ignoble beginning. It was an important site located along the vital route north from Puget Sound into the Strait of Georgia, the sheltered portal at the southern end of the Inside Passage to Alaska.

The Point Wilson Lighthouse, marking the entrance to Admiralty Inlet, was built by the Lighthouse Service. At 51 feet above the water, the lens is the highest of all the lighthouses on Puget Sound. The 1914 lighthouse replaced an earlier wooden lighthouse which was con¬structed in 1879. The Point Wilson Lighthouse, lo¬cated in Fort Worden State Park near Port Townsend, is on the National Register of Historic Places and the Washington State Heritage Register. It is one of the most important navigational aids in Washington, a link connecting Puget Sound and the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

This article is an attempt to correct some of the myths that have been perpetuated for some time concerning lighthouse locations, lighthouse structures and, most importantly, the illuminating apparatus used in them. I have little expectation that I will put an end to such tales but if I can correct any of the confusion that exists about lighthouses then this will have been a worthwhile effort.

About 1876, the Lighthouse Service decided it would be a good idea to provide a small library at isolated stations to improve morale. The Annual report of that year States, "During the past year the board has collected fifty small libraries, consisting of about 40 volumes each, for use at the more isolated light stations. It is intended that each library remain about six months at a place, when it will be exchanged for another.

In October 1804, John Cooper (or Couper) sold four acres

of land, known as Couper’s Point to the government for one dollar.

Finally, three years later, an act passed on March 3, 1807, authorizing

$19,000 to build the lighthouse. This amount far exceeds

funds authorized for other lighthouses in this era. As an example, in

1806 $5,000 was authorized for each of the following lighthouses: on

Fairweather Island, Connecticut, and Franklin Island, Maine, and a

two-towered station at Chatham, Massachusetts. The extraordinary